Freediving has a reputation of being an extreme and dangerous sport that claims lives. Movies, from classic The Big Blue to the recent Netflix releases such as The Last Breath and No Limit, contributed a lot to this view. We’ll go over the movies in some of our future posts. For now, let’s keep in mind that tragic events make it into movies because they’re dramatic and exceptional. Freedivers don’t usually die by the dozen. And whether freediving is dangerous largely depends on how safely it is practiced. Most of the risks freedivers really face during their routine training can be avoided. In this article, we suggest exploring which risks they are and what can be done to prevent them. Let’s try and build a better and happier image of this sport we love!

1. Loss of motor control

Loss of motor control (LMC for short), also known as samba, is involuntary muscle contractions in limbs, shoulders, and neck. They occur when the area in your brain responsible for motor control doesn’t get enough oxygen. LMC is a sign of acute hypoxia and may be followed by a blackout. In any case, it means you’ve pushed yourself too far.

How to avoid: If you’ve noticed signs of LMC in yourself, stop training for the day. Not even dry static! If you’ve noticed signs of LMC in your buddy, make them stop freediving immediately and rest. It might not be an easy task: hypoxia affects people’s critical thinking, and they may refuse to accept something’s wrong. Be persuasive. To avoid acute hypoxia in general, don’t push your limits too far too fast. Increase your depth, distance, or dive time gradually. Always finish your dive with proper recovery breathing. Listen to your body and stop training while you still feel fine and strong.

2. Blackout

When the level of oxygen in the blood feeding your brain drops even lower, your body goes to power-saving mode and switches off consciousness (as it’s very power-consuming and non-essential). This is called a blackout. It may be preceded by signs of acute hypoxia such as confused mind, tunnel vision, or LMC. It’s not dangerous per se: during a blackout, a laryngospasm occurs, which means our vocal folds contract to prevent water from coming in. It may last for up to several minutes, giving the buddy enough time to get the unfortunate diver to the surface, remove their mask, and expose their airways to air. Typically, the freediver then starts breathing and regains consciousness. But if there’s no reliable buddy, a blackout may result in drowning. This is why the first rule of freediving says: Never freedive alone.

How to avoid: Same as with LMC, monitor your condition and stop training when you get hypoxic. Don’t push yourself; don’t dive if you’re cold, sick, or exhausted. Recovery breathing is paramount. There are people who say blacking out gives room for analysis, but the only conclusion drawn from such analysis is that they’ve gone far beyond their limits. We can only develop when we have a resource. Blacking out means you’ve run out of your resources, and there’s nothing to develop. It always throws you back.

Specific risks freedivers face are those related to pressure. As we dive, we’re exposed to the atmospheric pressure and the pressure of the water above us. Luckily, our bodies are non-compressible. Gases, however, are. So if there’s a gas trapped in an enclosed space in our body, increasing pressure will cause it to decrease its volume, which may lead to unpleasant sensations and injuries. Let’s go over these pressure-related injuries and find out how to avoid them.

3. Ear barotraumas

Your middle ear is filled with air and surrounded by bones, so it can’t change its volume as the air inside compresses. This leads to our eardrum bending inwards and eventually rupturing. Luckily, our middle ear is connected to our nasal cavity by an auditory tube, also known as the Eustachian tube. As we descend, we use equalization techniques to transport air to our middle ear through our Eustachian tubes, thus balancing the pressure. The [roblem starts if for some reason we’re unable to equalize. The problem may also occur at the other end: if your hood is too tight, it creates one more enclosed space between your external auditory canal and your middle ear. You can’t equalize that space, which may also injure your middle ear. If you force equalization and apply too much pressure, or your equalization is incomplete, you may also injure your inner ear. These injuries are quite painful, cause vertigo, and may lead to permanent ear loss. So equalization isn’t something to be taken lightly. A ruptured middle ear may take months to heal and never heal properly.

How to avoid: Equalize your ears at the right time, before you feel any discomfort, let alone pain. If you do have an unpleasant sensation, stop the dive and turn. Yes, even if your goal is just in a couple of meters! Never force equalization. If it doesn’t work, it doesn’t work. Don’t dive when you have a cold, as your Eustachian tubes may be swollen, hindering equalization. Add water to your hood before every dive.

4. Sinus squeeze

Your sinuses are air-filled spaces around your nasal cavity: two above the eyes, two between them, two behind, and two under. Usually they equalize automatically as they’re not enclosed. Problems begin if they’re swollen. Then the passage of air through them becomes difficult, and equalization becomes slow or impossible. As they’re surrounded by bones, you may experience pain and bleeding.

How to avoid: Nothing new here. Don’t dive if your nose is congested, equalize regularly, and turn if you feel any pain.

5. Reverse block

We usually don’t get an ear barotrauma on the way up, because our Eustachian tubes open automatically under the pressure of the expanding air in our middle ear. But when they don’t open, for example, if filled by mucus or swollen, the air is trapped. As the pressure decreases, it expands, causing your poor ear drum to stretch the other way. This can also get very painful and lead to it rupturing.

How to avoid: Guess what? Don’t dive when you have a cold or any ear, nose, or throat infection. If you do get a reverse block, stop the ascent, make swallowing movements, nod and turn your head, move your lower jaw, and ascend slowly. In the worst case, nothing will help. Accept it.

6. Lung squeeze

Your lungs are filled with air, but you don’t need to equalize them as they’re compressible. But if your diaphragm is not elastic enough, your ribs aren’t flexible, or you’re tense, your ribcage turns into yet another enclosed cavity. Then, as the volume of air in your lungs decreases, the vessels may get injured. Depending on the severity of the lung barotrauma, you may feel short of breath and tired, be unable to make a full inhale, and spit or cough up blood. If any of the symptoms occur, stop freediving immediately, get out of the water, and take a break (from any sport) until you fully recover. This might take weeks, but returning to training before your lungs fully heal may lead to permanent damage. The only casualty that occurred in-competition was related to a repeated severe lung barotrauma.

How to avoid: Always increase your depth gradually. Don’t dive to a new depth before you fully master your previous one. Don’t dive if you feel sick. Turn immediately if you get contractions on your way down. Relax as you dive and don’t tense up your intercoastal muscles, shoulders, or neck. Work on your chest and diaphragm flexibility. Regularly stretch. Don’t make any quick abrupt movements at depth.

7. Eye squeeze

Another enclosed area filled with air is your mask. As you dive, it will suck on to your face, causing bruises and an eye squeeze unless you equalize it. An eye squeeze doesn’t cause pain or have any detrimental effect on your eyesight (provided you don’t get it repeatedly), but you’ll look like you have two tomatoes instead of eyes. Still, that may come in handy for a Halloween party.

How to prevent it: Equalize your mask. Don’t dive deeper than 3 meters in your goggles as there’s no way to equalize them, or if you do, fill them with water.

8. Decompression illness

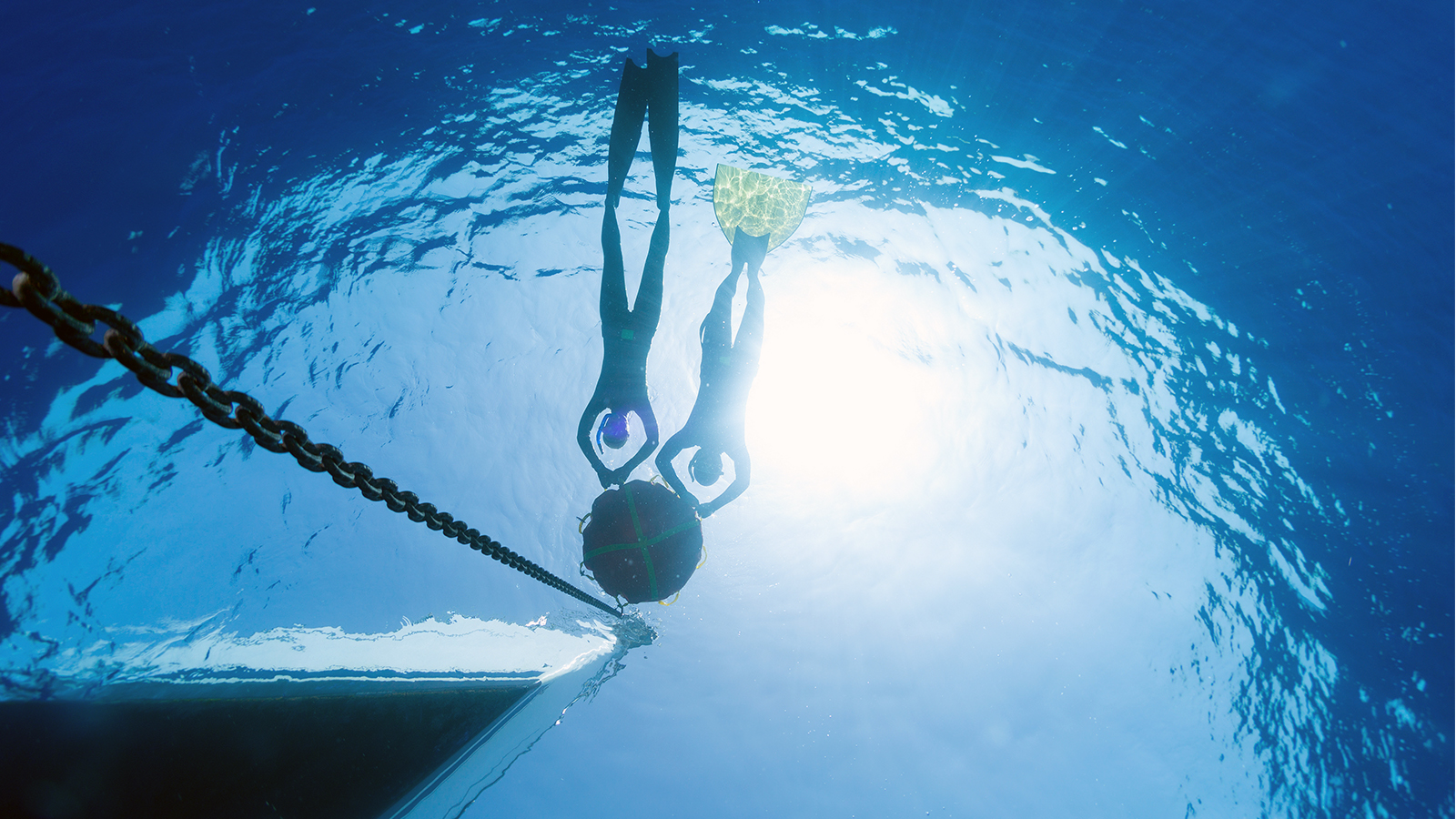

The air we breathe consists of nitrogen, oxygen, and other gases. As we descend, their concentration in our body increases due to increased pressure. If our body doesn’t have enough time to get rid of all the nitrogen, during the ascent, it may form bubbles which damage blood vessels and tissues. In worst cases, this may lead to paralysis or a stroke. DCI is much less common in freedivers than in scuba divers, because freedivers dive on a single breath, while scuba divers add more and more nitrogen to their blood with every breath they take underwater. This is why freedivers can ascend much faster than scuba divers, who need decompression stops. This is also the reason why safety divers at competitions are all freedivers rather than scuba divers. However, there have been reports about DCI in freediving, including the recent case in Panglao. All of them have been related to repeated deep dives.

Signs and symptoms of DCI, such as muscle and joint pain, impaired vision, and partial paralysis, usually appear within 15 minutes after surfacing but may occur up to 36 hours later. It’s crucial to start treatment as soon as possible. Delays may lead to permanent injuries.

How to prevent: There’s not much research in this field, but the consensus so far is: Always keep the surface interval between dives. It’s better to make your buddy wait a couple more minutes than get paralyzed for the rest of your life. Only perform one deep dive (>60 m) in 24 hours. If you mix freediving and scuba diving, wait until the end of the no-flight period after your scuba dive before freediving. Breathe oxygen if you suspect any symptoms of DCI and go to the nearest decompression chamber. This is quite costly, so make sure you have an appropriate insurance policy.

Freediving can be dangerous, but it doesn’t have to. There are safety rules; adhere to them. Regularly update your First Aid skills and make sure your buddy does the same. And set your ego aside. Remember there are truly important things, like your life, health, and well-being. Numbers are unimportant. Even competitive freediving is still a game.